When you hear someone say they have COPD, it’s easy to think of it as one thing - a general lung problem. But that’s like calling all heart disease the same. In reality, chronic bronchitis and emphysema are two very different diseases that often show up together under the COPD umbrella. They damage the lungs in opposite ways, cause different symptoms, and need totally different treatments. If you or someone you care about has COPD, understanding the difference isn’t just helpful - it’s life-changing.

What’s Actually Happening in the Lungs?

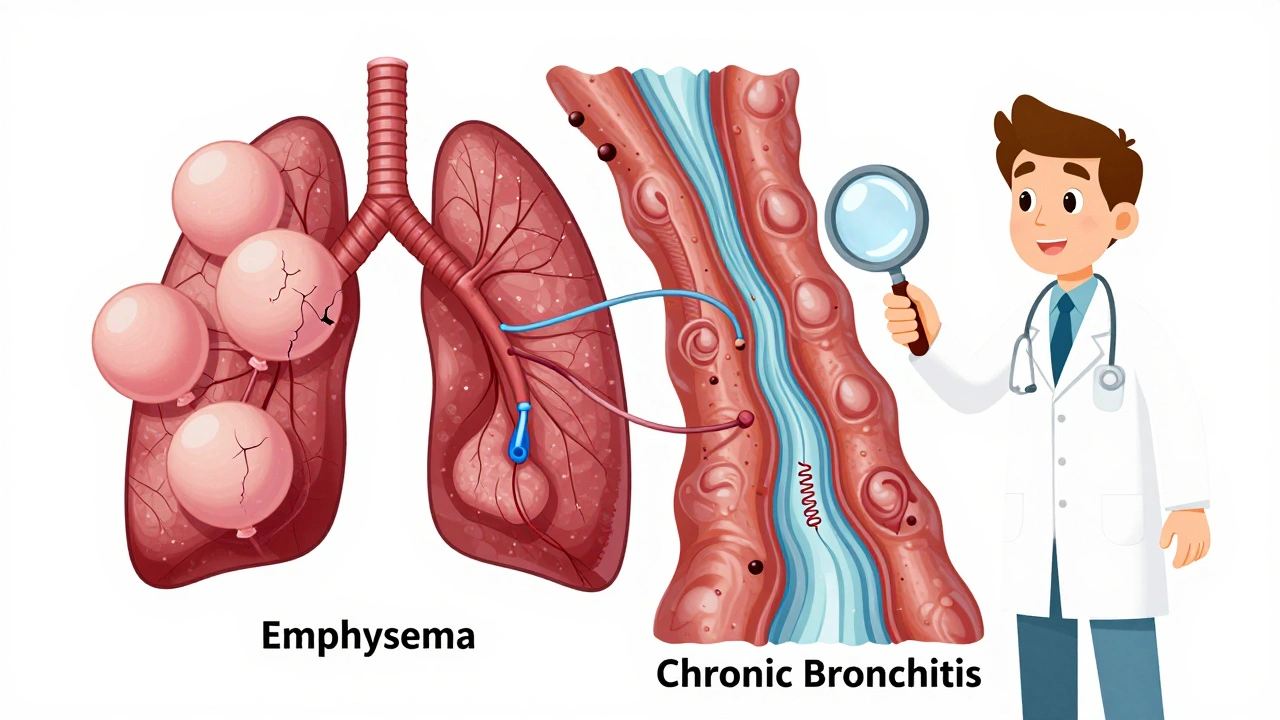

Think of your lungs like a tree. The bronchial tubes are the branches, and the alveoli - tiny air sacs - are the leaves where oxygen enters your blood. In chronic bronchitis, the branches swell up, get clogged with thick mucus, and stop working right. In emphysema, the leaves fall apart and the tree can’t hold its shape.

Chronic bronchitis is defined by a daily cough that brings up mucus for at least three months in a row, for two years straight. That’s not just a cold that won’t quit - it’s your body’s airways overproducing mucus because of long-term irritation, usually from smoking. The mucus glands in your airways grow by 300-500%, pumping out 100-200 mL of mucus a day (normal is 10-100 mL). The tiny hairs (cilia) that normally sweep mucus out become paralyzed. So mucus piles up, blocks airflow, and makes breathing feel like trying to suck air through a straw stuffed with cotton.

Emphysema is more like structural collapse. The walls between the alveoli break down - the elastin and collagen fibers that keep them springy are destroyed. This creates giant, useless air spaces instead of thousands of small, efficient ones. The lungs lose their natural recoil, like a deflated balloon that won’t bounce back. You’re left with less surface area to absorb oxygen. In advanced cases, oxygen diffusion drops by 40-60%. That’s why people with emphysema feel out of breath even when sitting still.

How Do the Symptoms Differ?

The way these two conditions make you feel is night and day - and doctors have names for them.

Emphysema patients are often called “pink puffers.” They’re usually thin, breathe fast (25-30 breaths per minute), and have a barrel chest from overworking their lungs. Their skin stays pink because they’re hyperventilating to keep oxygen up. But they can barely speak in full sentences - five or six words at a time before needing to gasp. Their biggest problem? Air hunger. It’s not the mucus that’s choking them - it’s the feeling that no matter how hard they breathe, they can’t get enough air.

Chronic bronchitis patients? They’re the “blue bloaters.” Their skin has a bluish tint because oxygen levels are low (SpO2 85-89%). Their ankles swell from heart strain caused by long-term low oxygen. They’re often heavier, with a persistent cough that brings up mucus - sometimes 30-100 mL a day. Many describe waking up needing to clear their lungs for 20-30 minutes. One patient on Reddit measured his morning mucus in a cup: 100 mL, every day, for eight years. Winter makes it worse - 68% of these patients have flare-ups when it gets cold.

How Do Doctors Tell Them Apart?

It’s not just about symptoms. Pulmonary function tests show clear differences.

For chronic bronchitis, the main clue is airflow obstruction - the FEV1/FVC ratio is below 70%, meaning you can’t blow air out fast enough. But the DLCO (diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide) stays normal or only slightly low. That’s because the alveoli are still mostly intact - it’s the tubes that are clogged.

For emphysema, the DLCO is the giveaway. It drops below 60% of what’s expected. That’s because the lung tissue itself is destroyed. CT scans show it too: emphysema shows dark, low-density patches covering more than 15% of the lungs. Chronic bronchitis shows thickened airway walls - over 60% wall area on expiratory scans.

Another test: the 6-minute walk. Emphysema patients drop their oxygen below 88% within two minutes. Bronchitis patients keep their oxygen up - but they stop walking because they’re out of breath from mucus and airway resistance, not from lack of oxygen.

Treatment Isn’t One-Size-Fits-All

Here’s where it gets critical. Giving the same treatment to both conditions doesn’t just waste time - it can hurt.

For chronic bronchitis, the goal is to clear mucus and reduce inflammation. Mucolytics like carbocisteine reduce flare-ups by 22%. Hypertonic saline nebulizers thin mucus - 73% of users report easier clearing. Roflumilast, a pill that targets lung inflammation, cuts exacerbations by 17.3% in patients who have two or more flare-ups a year. But here’s the catch: inhaled steroids - often used in asthma - increase pneumonia risk by 40% in bronchitis patients. So guidelines now recommend LAMA/LABA inhalers (like tiotropium and formoterol) as first-line.

For emphysema, the focus is on saving lung volume and improving airflow. Bronchoscopic lung volume reduction - using valves or coils to collapse damaged areas - helps 65% of patients improve their breathing and walking distance. Endobronchial valves increased 6-minute walk distance by 35% in one trial. For the rare 1-2% with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, weekly protein infusions slow lung damage. In 2023, the FDA approved an inhaled version of this therapy - it boosted FEV1 by 20% in 12 months.

And yes, smoking cessation is non-negotiable for both. But beyond that? Their treatment paths diverge sharply.

Who Gets Which Type - And Why?

Most people with COPD have a mix of both. But one tends to dominate. Emphysema is more common in younger, thinner smokers with a history of heavy smoking. It often runs in families - especially with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Chronic bronchitis hits more often in older adults, especially those with long-term exposure to fumes, dust, or secondhand smoke. It’s also more common in women - possibly because their airways are smaller and more sensitive to irritation.

But here’s the twist: only 15% of severe COPD patients have pure bronchitis or pure emphysema. The rest are a blend. That’s why doctors now avoid calling someone just a “pink puffer” or “blue bloater.” It’s too simple. But that doesn’t mean the differences don’t matter. Even in mixed cases, one component usually drives the main symptoms - and that’s what guides treatment.

What Does This Mean for Daily Life?

Living with either condition changes everything.

Emphysema patients often avoid social events because talking takes too much effort. They carry portable oxygen, which limits mobility - even if it’s a small concentrator delivering 2-4 liters per minute. They’re more likely to get depressed from feeling trapped in their own bodies.

Chronic bronchitis patients spend hours on chest physiotherapy, using devices to shake mucus loose. Many skip work because coughing fits are embarrassing. They’re more likely to get pneumonia - and more likely to be hospitalized for it. One patient in a 2023 survey said, “I keep a bucket by my bed. If I don’t cough it out, I can’t sleep.”

Both groups struggle with medication routines. Sixty-eight percent of bronchitis patients say taking four to six inhalers a day is overwhelming. Fifty-two percent of emphysema patients say oxygen tanks make them feel like a prisoner in their own home.

What’s New in Treatment?

Things are changing fast. In 2024, Europe approved an acoustic device that vibrates mucus loose - it cut exacerbations by 32%. In the U.S., bronchoscopic thermal vapor ablation is showing 78% success in reducing emphysema damage over two years. Researchers are testing new drugs that target TMEM16A channels - the same ones that control mucus production - which could be a game-changer for bronchitis.

The NIH is now tracking blood markers like eosinophils (above 300 cells/μL) to predict who will respond to biologic therapies. And in 2022, the FDA started requiring all new COPD drug trials to report results separately for each phenotype. That’s a huge shift - it means future meds will be designed for specific types of COPD, not a one-size-fits-all approach.

Where Do You Go From Here?

If you’ve been diagnosed with COPD, ask your doctor: “Which part is driving my symptoms - the mucus or the destroyed lung tissue?” Don’t accept a generic answer. Request a DLCO test. Ask about CT scans. Find out if you’re a candidate for lung volume reduction or mucolytics.

Join a support group. The COPD Foundation has over 200 local chapters. People who spent six months in their programs reported better self-management and fewer hospital visits.

And remember: COPD isn’t a death sentence. It’s a condition that responds to precision care. The more you understand your specific type - whether it’s bronchitis, emphysema, or both - the more control you have over your breathing, your life, and your future.

Can you have emphysema without chronic bronchitis?

Yes. While most people with COPD have features of both, about 15% have a clear dominant phenotype. Pure emphysema is more common in younger smokers with genetic risks like alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. These patients often have severe shortness of breath with minimal cough or mucus. Their lung scans show widespread destruction of alveoli, but airway walls remain relatively normal.

Is COPD the same as asthma?

No. Asthma is reversible airway narrowing caused by inflammation and muscle tightening. COPD is irreversible damage - either from destroyed lung tissue (emphysema) or thickened, mucus-clogged airways (chronic bronchitis). Asthma usually starts in childhood, while COPD develops after decades of exposure to irritants like smoke. Asthma responds well to steroids; COPD often doesn’t, and steroids can even increase pneumonia risk in bronchitis patients.

Why do some COPD patients need oxygen all the time?

Oxygen therapy is prescribed when blood oxygen levels stay low even at rest - usually below 88%. This is more common in advanced emphysema, where damaged alveoli can’t transfer oxygen into the blood. It’s also seen in chronic bronchitis patients with severe hypoxemia and heart strain. Long-term oxygen therapy can extend life and improve quality of life, but it doesn’t fix the underlying damage - only supports it.

Can quitting smoking reverse COPD?

No - the damage from emphysema and chronic bronchitis is permanent. But quitting stops the disease from getting worse faster. Studies show people who quit after diagnosis slow their lung decline by 50%. Their cough and mucus improve within weeks. Their risk of pneumonia and hospital stays drops sharply. It’s the single most effective thing you can do.

Are there any new drugs for COPD in 2025?

Yes. In 2023, the FDA approved an inhaled form of alpha-1 antitrypsin replacement for genetic emphysema - it improved lung function by 20% in 12 months. In 2024, a new dual PDE3/4 inhibitor called ensifentrine became available in Europe, offering better bronchodilation and anti-inflammatory effects than older drugs. For chronic bronchitis, novel mucoregulators targeting TMEM16A channels are in Phase 3 trials and could reduce mucus production by up to 40%.

Dec, 1 2025

Dec, 1 2025

James Kerr

December 3, 2025 AT 03:28Man, I’ve seen my uncle go through this - pink puffer through and through. Used to carry his oxygen tank like a backpack to the grocery store. Said he felt like a sci-fi robot. But he quit smoking in ’19 and now he walks his grandkids to school. Still wheezes, but he’s alive. That’s the win.

Rashi Taliyan

December 4, 2025 AT 03:13Oh my GOD. I just read this and I’m crying. My aunt was a blue bloater - every morning, she’d cough into a jar like it was a ritual. She’d say, ‘This is my life’s soup.’ I didn’t know it had a name. This post? It’s like someone finally wrote a poem about her suffering.

sagar bhute

December 5, 2025 AT 00:21This is just another overhyped medical blog. Everyone knows COPD is just smokers’ disease. Stop pretending it’s complicated. Quit smoking. End of story. All this ‘phenotype’ nonsense is just pharma’s way to sell more inhalers.

Kara Bysterbusch

December 5, 2025 AT 03:36As a pulmonology nurse with over 22 years in clinical practice, I must commend the precision of this exposition. The delineation between DLCO anomalies and airway remodeling is not merely academic - it is clinically transformative. The misapplication of inhaled corticosteroids in chronic bronchitis remains one of the most preventable iatrogenic harms in pulmonary medicine. Furthermore, the emerging TMEM16A modulators represent a paradigm shift in mucoregulatory pharmacology - a field long neglected in favor of bronchodilator-centric paradigms. One must acknowledge that phenotypic stratification is no longer optional; it is the ethical imperative of 21st-century respiratory care.

Gavin Boyne

December 5, 2025 AT 10:01So let me get this straight - we’ve got people with lungs like deflated balloons, and others with airways clogged like a sink full of oatmeal. And we’re still calling it ‘COPD’ like it’s one big, sad bucket of confusion? 🤦♂️

Meanwhile, Big Pharma’s selling two different drugs, two different inhalers, two different insurance codes… and the patient just sits there with six pills in their hand wondering why they can’t just get one magic bullet.

Maybe the real disease isn’t in the lungs - it’s in the medical system’s refusal to admit that biology is messy. We love our boxes. But lungs? They don’t read DSM manuals.

Rashmin Patel

December 6, 2025 AT 13:49OMG I’m so glad someone finally explained this! I’ve been telling my dad for years that his ‘coughing fits’ aren’t just ‘smoker’s cough’ - they’re chronic bronchitis, and he needs mucolytics, not just more Ventolin 😭

He’s 68, smokes 2 packs a day, and still says ‘I’ve lived this long, why stop?’ But now I’ve printed out this whole article and taped it to his fridge with a sticky note: ‘Dad, your lungs are not a smokestack.’ 🤣

Also, the 100mL mucus cup story? That’s my uncle. He kept it as a trophy. I swear, I’m not joking. He said, ‘If I can’t stop, at least I can measure it.’

And yes, the new acoustic device? I’m begging my doctor to refer me. I saw a video of it - it looks like a tiny, angry UFO for your chest. I want one.

Cindy Lopez

December 7, 2025 AT 11:46There is a comma splice in the third paragraph: ‘The mucus glands in your airways grow by 300-500%, pumping out 100-200 mL of mucus a day (normal is 10-100 mL). The tiny hairs (cilia) that normally sweep mucus out become paralyzed.’ The second sentence is a fragment. Also, ‘SpO2 85-89%’ should be ‘SpO₂ 85–89%’ with subscript and en dash. This is a high-quality article, but sloppiness undermines credibility.

bobby chandra

December 8, 2025 AT 01:02Let’s be real - this isn’t just medicine, it’s a war. Your lungs are fighting a losing battle against decades of smoke, dust, and bad choices. But here’s the twist: you still get to pick your weapon.

For the blue bloaters? Fight with mucolytics, chest physio, and hydration. For the pink puffers? Oxygen, lung volume reduction, and don’t you dare skip your rehab.

And yeah, quitting smoking isn’t a suggestion - it’s your last standing ovation. If you’re still smoking, you’re not just killing your lungs - you’re disrespecting everyone who’s fighting to breathe.

Don’t wait for a hospital bed to wake up. Your next breath? Make it count.

vinoth kumar

December 9, 2025 AT 22:26I work in a clinic in Delhi and we see so many patients with this - especially women who cook over wood stoves. They don’t call it COPD. They say ‘chest sickness’ or ‘dum ki bimari’. But this breakdown? I printed it and gave it to all my patients. One lady said, ‘So I’m not just weak - my lungs are broken like a rusted pipe?’ I said yes. She cried. Then she quit smoking. We need more of this - simple, real, human.

shalini vaishnav

December 11, 2025 AT 15:31How can Americans have such advanced medical knowledge yet still allow smoking in the 21st century? In India, we have strict anti-smoking laws - public smoking is punishable by fine and mandatory counseling. We don’t need fancy DLCO tests when we prevent the disease at the source. This article reads like a luxury problem of a rich country that won’t enforce basic public health. Shame.